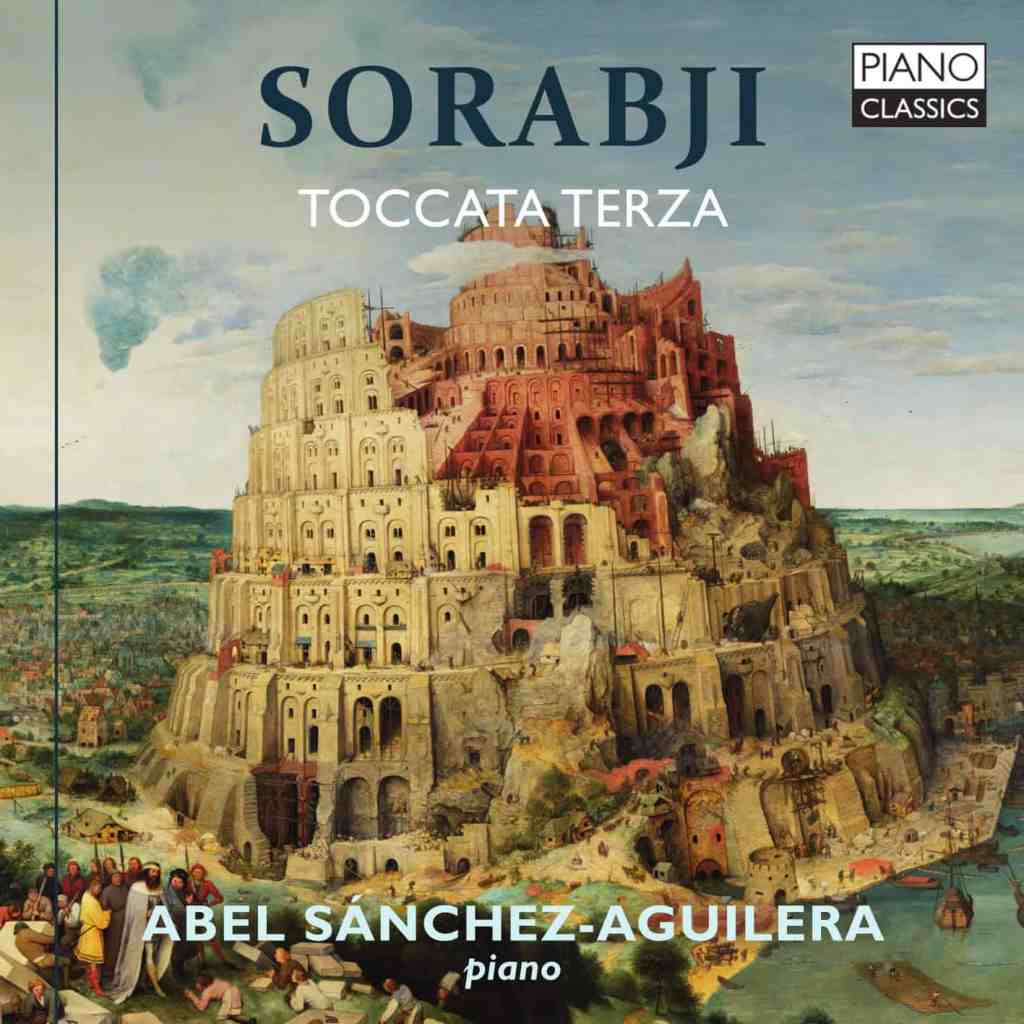

A lost work rediscovered: Sorabji’s Toccata terza

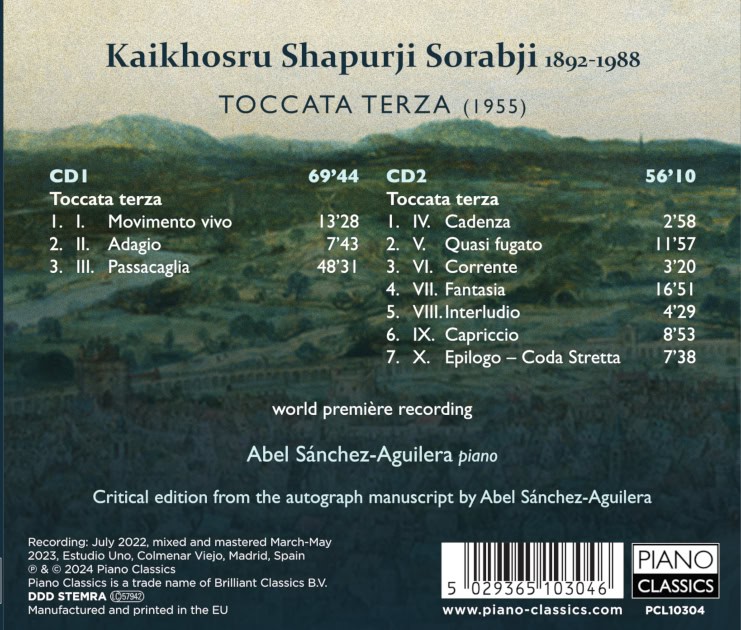

In the morning of 25 September 2019 I received an e-mail from Alistair Hinton, curator of the Sorabji Archive, asking if I would be interested in performing Toccata terza. This proposition was extremely intriguing. The autograph of this unpublished composition from 1955 had been missing since the early sixties. The score had been gifted by Sorabji to the dedicatee, American critic Clinton Gray-Fisk, together with several earlier manuscripts, all of which went missing after Gray-Fisk’s death and were generally believed to have been lost and possibly destroyed. Some of these manuscripts, such as Piano Sonata ‘no. 0’ and Toccatinetta sopra C.G.F., surfaced decades later; however, the whereabouts of Toccata terza remained unknown and it was considered to be a lost work until it was suddenly discovered in a private collection.

The gradual rediscovery of Sorabji’s music over the last decades has revealed a vast piano repertoire of unusual originality and exuberance. His music unites opposite elements in enormous, coherent wholes: languorous lyricism and fiery virtuosity, East and West, post-impressionistic colour and complex polyphony. His longer works challenge the limits of the performer and invite the listener to a new perception of time.

Sorabji composed four piano toccatas, large-scale compositions in multiple sections built upon the basic scheme of prelude, passacaglia and fugue. They seem to look back to the examples of Bach and Busoni, reinvented in Sorabji’s personal language and expanded to monumental proportions. Notwithstanding their complexity, several features make them particularly effective and accessible to the listener. They make use of familiar procedures – such as the variation and the fugue –, establishing clear links with tradition. The variety provided by the contrasting movements is given cohesion by a simple, easily identifiable musical idea, from which the entire musical edifice unfolds.

In Toccata terza this basic, unifying idea is a three-note motif stemming from the dedicatee’s initials (C.G.F), thus partaking in the centuries-old game of deriving musical themes from personal names. This exceedingly simple material forms the basis for the themes of the Adagio, the passacaglia and the fugues and recurs often throughout the work, infinitely varied, as a dominant idea. Some version of the CGF motif sounds emblematically at the beginning of every movement – except the ninth, where it is placed at the end. It implies C major as a tonal centre; the opposition between this and the black-key centres C# and F# is of fundamental dialectical importance on both a small and a large scale.

Toccata terza, written in ten movements, is one of the most ambitious piano works of the 1950s. It expands the vocabulary of the two earlier toccatas by means of a more audacious harmonic language – quartal harmony is implicit in the main motif – and an unusual, asymmetric formal plan in which a gigantic passacaglia dominates the first half, a fugue of modest proportions is placed in the middle, and the last five movements form an extended epilogue.

An initial statement of the CGF motif in powerful chords introduces a vibrant virtuoso movement (Movimento vivo). This is a virtually uninterrupted moto perpetuo exploring every register of the keyboard and various degrees of textural density. The main motif is developed extensively in the first few pages and returns at various points throughout, notably at the massive ending.

The Adagio takes the place of the chorale prelude in the other toccatas, but is a free fantasy rather than a variation movement. The theme – derived from the CGF motif – is initially stated pianissimo, in one voice, like a soft carillon. The number of parts gradually increases into a multilayered superposition of several lines of chords spread over the entire keyboard, leading to a shattering climax (marked Gigantesco) where the theme returns in a series of canonic imitations. The final passage is a powerful affirmation of the key of C major, ultimately obscured by a chord containing ten different pitches.

The Passacaglia, at nearly fifty minutes, is by far the longest section in the work, and a fierce challenge to the performer. A twelve-note theme derived from the CGF motif is followed by 102 variations exhibiting boundless imagination and variety. The intensity of the music grows in successive waves punctuated by interludes of transient calm, including several Sorabjian nocturnes in miniature and an expressionistic waltz, before building up to a cataclysmic ending.

The Cadenza is a brief virtuoso section, featuring very quick figurations, that dissipates the tension of the passacaglia and serves as prelude to the fugue. Here the thematic notes CGF are presented vertically, in chordal form, which gives the harmony a quartal flavour.

The double fugue that follows (Quasi fugato) exhibits many characteristics of a traditional fugue: brief subjects with answers in related keys; use of stretti, inversion and augmentation; superposition of the two subjects in the second fugue. Both subjects are further variants of the CGF motif. Though the movement is marked Deciso, I prefer to play the first fugue in a slow, solemn tempo, reserving a more energetic approach for the rhythmically-driven second fugue. A massive coda of the highest polyphonic density concludes the movement combining multiple versions of the two subjects.

The phantasmagorical Corrente bears no relation – or a humorous one at the most – to the homonymous ancient dance. The term seems to allude to the rapid, ceaseless motion of quavers in both hands, which follow independent paths across the entire compass of the keyboard. It has the quality of an étude, posing challenges in hand coordination, softness and evenness of touch in a fast tempo.

The Fantasia, an extended slow movement in Sorabji’s idiosyncratic ‘hothouse nocturne’ style, features sinuose chromatic melodies accompanied by complex arpeggiated patterns and layers of profuse decoration. The atmosphere is soft and impressionistic, but it builds up to several massive climaxes before the music ultimately evaporates in a slow arpeggio.

The calm is broken by the Interludio, another brief, cadenza-like movement consisting of rapid scale and arpeggio figurations in semiquavers. Bitonal and polychordal sonorities abound, recalling some of Busoni’s most experimental pages, such as those in Sonatina Seconda. This leads directly to the eccentric Capriccio, a very fragmented episode of restless character and irregular rhythms. It contains one of the most radical passages ever conceived by Sorabji, a brutal hammering of a repeated, harsh dissonance in the extreme registers of the keyboard. A brief Nexus – a soft reminiscence of the chords that opened the work, stating the CGF motif – connects without interruption with the Epilogo. This begins as a contemplative, poetic meditation that builds up to a short-lived ecstatic climax before collapsing into a tense Coda-stretta, a brief polyphonic development of the passacaglia theme.

The final cadence seems to take us back to the very beginning, closing the circle. It is, however, a dark reflection of the opening chords heard two hours earlier, this time ending tragically in D# minor, a somber key that negates expectations of any of the tonal centres previously established and eludes an anticipated luminous ending in C or C# major. Like Opus Clavicembalisticum, the work ends in Sorabji’s characteristic, Mephistophelian mood (“Ich bin der Geist, der stets verneint!” – “I am the spirit that denies!”).

© Abel Sánchez-Aguilera, 2023

PRESS REVIEWS

“Sánchez-Aguilera consigue que esta no sea solo una primera grabación de la obra, sino una versión de referencia para futuras interpretaciones. Su capacidad para jugar con los rangos dinámicos y el timbre confieren un carácter orquestal a la partitura en puntos como el Adagio o la Fantasia. La claridad y ligereza de su toque se observan en la Cadenza o el Corrente (…). Todos estos rasgos se combinan en el número central, una Passacaglia de casi cincuenta minutos de duración en la que (…) Sánchez-Aguilera hace alarde de su habilidad para manejar las olas de intensidad que dan forma a este número y alcanza el clímax, sin duda uno de los puntos culminantes del disco, de manera brillante y rotunda. Para cuando alcanzamos el Epílogo de la Toccata estamos ya rendidos a la música de Sorabji y convencidos de que Sánchez-Aguilera es uno de sus grandes intérpretes.”

Richard Whitehouse

International Piano

“Sánchez-Aguilera thrives on the conceptual and technical challenges of this music. As with his reading of the rather longer Toccata seconda (also on Piano Classics), a virtuosity that never takes itself for granted is continually geared towards the music’s essence. Rarefied though Sorabji’s music may be, it can be engrossing and communicative when interpreted with this degree of authority and insight.”

Phillip Scott

Fanfare

“Again, Sánchez-Aguilera scales this new edifice with aplomb, backed by his analytical intelligence, stamina, and sheer keyboard facility. It is a truly impressive feat.”

Jed Distler

Gramophone

“There’s a lightness and playfulness throughout the opening Movimento vivo.[…] Part of this is due to Sánchez-Aguilera’s supple navigation of the rapid scales and clotted chords, plus the transparency resulting from his discreet pedalling. […] Certainly this pianist commands the technical wherewithal for going beyond reams of notes in pursuit of the music, along with his affinity for and gigantic commitment to Sorabji’s aesthetic.”

Paul RW Jackson

Music Web International

“[Abel Sánchez-Aguilera] delivers a performance of enormous clarity and subtlety […]. From the off, we know we are in safe hands with Mr Sánchez-Aguilera colouring every note and making every line sound clearly. There is no muddy pedalling or fudging of ideas here.

In Mr Sánchez-Aguilera’s hands it [the Interludio] sounds like joy but must be terrifying to play. [In the Capriccio] Once again, such is the pianist’s skill in colouring and dynamics that he makes what could be a brutal nightmare a quixotic dream […]. He is clearly very at home with Sorabji’s aesthetic.”

Remy Franck

Pizzicato

“Abel Sanchez-Aguilera contrasts the movements very well and plays in a stylish, lively and fluent manner, so that both the sensual beauty of the music and the rhythm are well served.”